If communal bikes can make it in New York, can they make it anywhere? Alta Bicycle Share aims to find out.

Alta Bike Share president Alison Cohen hopes New Yorkers take note of her 10,000 communal bikes.

Thanks to the advent of docking stations and fee-paying requirements, bike-sharing networks now thrive in cities around the world. Paris has about 20,000 community bikes. Hangzhou, China, boasts around 60,000. In both cities, the fleets are effectively cogs in metro mass-transit networks: They offer an alternative to taxis, or an efficient way for tourists to see the sights. That will be the case in New York, though emphasis will be placed on using the bikes as a "last mile" link for residents going to and from bus or train stops. "They're made for short trips," says Janette Sadik-Khan, New York's transportation commissioner, of the city's bikes. "They're for transportation, not recreation."

That stance is reinforced by Alta's fee structure: If you decide to use a city bike to tour Central Park for a day, you'll weep when you see the charge. New York's bike share, like the Alta-run systems in Washington, D.C., and Boston, relies on membership fees. In New York, you can join for the day ($9.95), week ($25), or year ($95). You ride free for 30 minutes at a time (or 45 minutes for annual members). After that, you're charged a hefty escalating fee for every additional half hour--for weekly members, first $4, then $13, then $25. Thus, a tourist could easily rack up a $150 tab over the course of a weekend. On the other hand, a commuter with a yearly membership who uses the bikes only for their last mile could make out well--paying just 26 cents a day, by the city's estimate.

It's too early to predict whether these pricing schemes will translate into U.S. bike-share systems that rival China's--or for Alta, a big business. Cohen is certain New York's system will make money; when the profits start arriving, they will be split between Alta and the city, which is investing in bike lanes to make the sharing plan viable. (Citibank and MasterCard get the benefit of free ads on docking stations and thousands of bikes.)

Still, the road to profitability is no sure thing. "The biggest challenge is balancing the system," Cohen explains. Bikes have to be where they're needed, when they're needed, which is why Alta will have fleets of vans moving them around the city at peak hours. Wireless links in the docking terminals will enable Alta to monitor vacancy, and many of the bikes will be equipped with GPS so Alta can analyze usage patterns and adjust allocations. (The terminals, which are solar powered, are movable, so demand in one location can easily be addressed.)

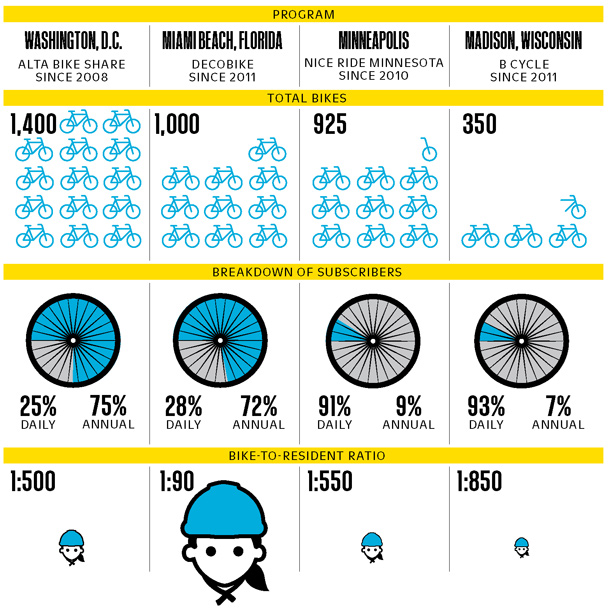

The juggling of 10,000 bikes will keep Alta busy. If the system grows in the coming years--as projections say it could--Alta will really have its hands full. Its vans, too. And that's just in New York. Cohen's crews will be doing the same thing in the other cities that have--or will soon have--Alta systems: The company is expanding its Boston and Washington, D.C., fleets, and just opened a 300-bike system in Chattanooga, Tennessee--"the first of its kind in a midsize southern city," says Cohen.

She adds that Chattanooga will be closely monitored as part of a data-collection experiment. "Tennessee is one of the most obese states in the U.S.," Cohen explains. Her company is working with the University of Tennessee to look at share data and measure its impact on Chattanoogans' lives. So the benefits from bike sharing could extend past the anticipated ones--cleaner air, easier commutes, giddier tourists. We may soon hear riders bragging about the calories they burned covering that last mile home.

Thanks to the advent of docking stations and fee-paying requirements, bike-sharing networks now thrive in cities around the world. Paris has about 20,000 community bikes. Hangzhou, China, boasts around 60,000. In both cities, the fleets are effectively cogs in metro mass-transit networks: They offer an alternative to taxis, or an efficient way for tourists to see the sights. That will be the case in New York, though emphasis will be placed on using the bikes as a "last mile" link for residents going to and from bus or train stops. "They're made for short trips," says Janette Sadik-Khan, New York's transportation commissioner, of the city's bikes. "They're for transportation, not recreation."

That stance is reinforced by Alta's fee structure: If you decide to use a city bike to tour Central Park for a day, you'll weep when you see the charge. New York's bike share, like the Alta-run systems in Washington, D.C., and Boston, relies on membership fees. In New York, you can join for the day ($9.95), week ($25), or year ($95). You ride free for 30 minutes at a time (or 45 minutes for annual members). After that, you're charged a hefty escalating fee for every additional half hour--for weekly members, first $4, then $13, then $25. Thus, a tourist could easily rack up a $150 tab over the course of a weekend. On the other hand, a commuter with a yearly membership who uses the bikes only for their last mile could make out well--paying just 26 cents a day, by the city's estimate.

It's too early to predict whether these pricing schemes will translate into U.S. bike-share systems that rival China's--or for Alta, a big business. Cohen is certain New York's system will make money; when the profits start arriving, they will be split between Alta and the city, which is investing in bike lanes to make the sharing plan viable. (Citibank and MasterCard get the benefit of free ads on docking stations and thousands of bikes.)

Still, the road to profitability is no sure thing. "The biggest challenge is balancing the system," Cohen explains. Bikes have to be where they're needed, when they're needed, which is why Alta will have fleets of vans moving them around the city at peak hours. Wireless links in the docking terminals will enable Alta to monitor vacancy, and many of the bikes will be equipped with GPS so Alta can analyze usage patterns and adjust allocations. (The terminals, which are solar powered, are movable, so demand in one location can easily be addressed.)

The juggling of 10,000 bikes will keep Alta busy. If the system grows in the coming years--as projections say it could--Alta will really have its hands full. Its vans, too. And that's just in New York. Cohen's crews will be doing the same thing in the other cities that have--or will soon have--Alta systems: The company is expanding its Boston and Washington, D.C., fleets, and just opened a 300-bike system in Chattanooga, Tennessee--"the first of its kind in a midsize southern city," says Cohen.

She adds that Chattanooga will be closely monitored as part of a data-collection experiment. "Tennessee is one of the most obese states in the U.S.," Cohen explains. Her company is working with the University of Tennessee to look at share data and measure its impact on Chattanoogans' lives. So the benefits from bike sharing could extend past the anticipated ones--cleaner air, easier commutes, giddier tourists. We may soon hear riders bragging about the calories they burned covering that last mile home.

No comments:

Post a Comment